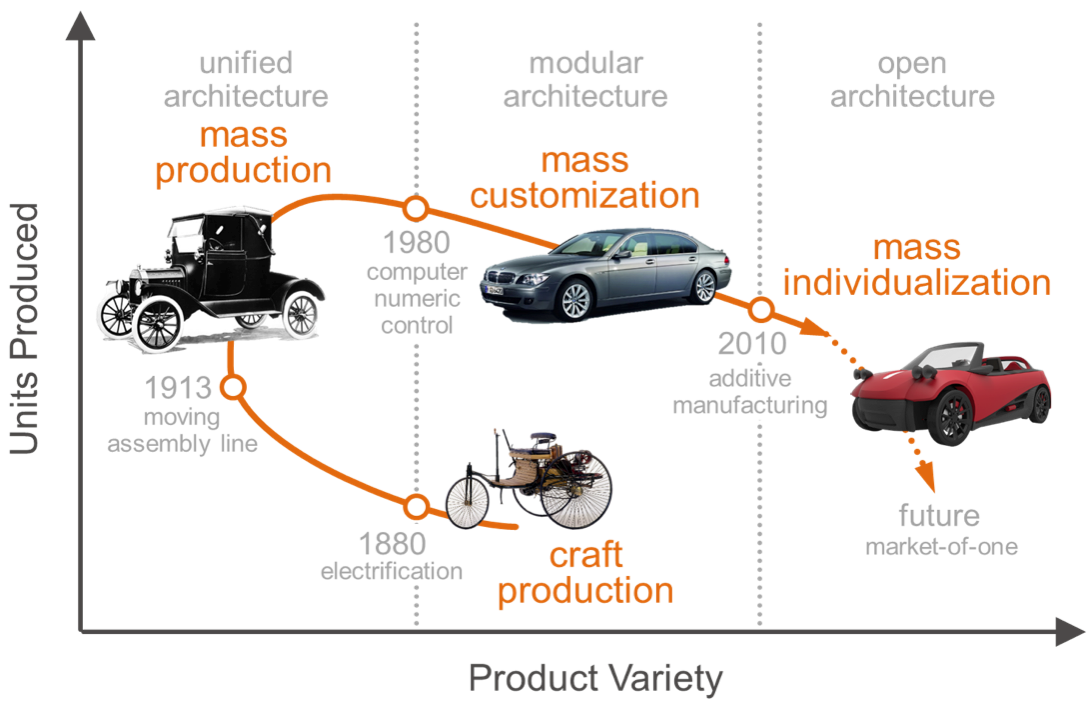

Today’s buzz around 3D printing promises a future of mass individualization, a market-of-one paradigm. The ability to make individually customized parts is a unique opportunity for additive manufacturing with 3D printers. On the opposite end of the spectrum, high-throughput manufacturing technologies such as injection molding offer the economies of scale for producing very large volumes of identical parts. But where is the cross-over point? Assuming we can make the same quality parts with either approach, there must be a lot size between one and many where the costs are equal. In our search for that point, we can start to explore opportunities where additive manufacturing is competitive with the existing paradigm (and where it could be competitive with the right materials).

(Image: Dane Boysen, Adapted from Koren, Y., et al. CIRP Annals-Manufacturing Technology 62.2 (2013):719–729.)

(Image: Dane Boysen, Adapted from Koren, Y., et al. CIRP Annals-Manufacturing Technology 62.2 (2013):719–729.)

As a first experiment, let’s explore the tradeoff between printing and molding a part. We’ll start with a very simple cost model that incorporates only three terms: setup cost, materials cost, and time cost. For the purposes of this first model, we’ll assume that this is the cost to the manufacturer, and that they already own the equipment to make the parts. For example, the setup cost for a traditional molding process includes the cost of designing and machining the mold. The setup cost for additive manufacturing includes the cost of designing the print file. The materials cost is hopefully self-explanatory, although it is important to note that the materials for additive manufacturing (photopolymers, filament, sintering powders, etc) are often orders of magnitude more expensive than their traditional analogs (thermoset resins, thermoplastic pellets, metal alloys, etc). The time cost is conceptually the same in each scenario, for example, the operator’s labor, electricity, and maintenance. Play around with these input parameters in this interactive graph below. (Best experienced on larger screens, not phones.)

See the Pen Mold vs. Print - First Order Cost Model by Raymond Weitekamp (@rawwerks) on CodePen.

This first-order cost model simply computes: (setup cost + materials cost + time cost)/units. The initial values are completely arbitrary — put your own in! Hover over the intersection to get the exact number of units. The functions will refresh as soon as you click away from an input. (Full disclosure: I’m having trouble formatting these plugins for mobile, I’m hoping a friendly wizard might fork for the win.)In this first model, we only took into account the cost of operating time. We ignored a very important tradeoff between the two processes: lead time vs. manufacturing time. For example, it can easily take ~6 weeks to have a mold machined. The tradeoff is that the mold will pump out a part every minute. In contrast, additive manufacturing has a shorter lead time, but much longer per unit cycling time. In this second model, we’ll add a burn rate, to account for the fact that we are spending money while we’re waiting for the job to be done.

See the Pen Mold vs. Print - Print Cost, Burn Rate and Manufacturing Time by Raymond Weitekamp (@rawwerks) on CodePen.

This model now includes a function for the time to manufacture (Y axis in weeks), by adding the lead & manufacturing times. The cost function now additionally accounts for our burn rate over this time. Again, play around with the inputs, or change the model yourself by forking this on CodePen. (Even better, teach me how to improve this.)

This second model can start to reveal much more about the tradeoffs between cost and speed. For example, it is easy to see how crucial the printing speed is to the economic feasibility of the fabrication run. This same kind of analysis could be easily extended to compare other manufacturing methodologies, such as CNC milling or metal casting.

Here’s the catch: all of this assumes that the part you are trying to manufacture can be 3D printed in the first place. This is a tall order — most 3D printers available today are not capable of directly making production-quality parts. Even with recent introductions of some new materials possibilities for additive manufacturing, there is still a long ways to go before 3D printing can render the full spectrum of possibilities available with traditional methods.

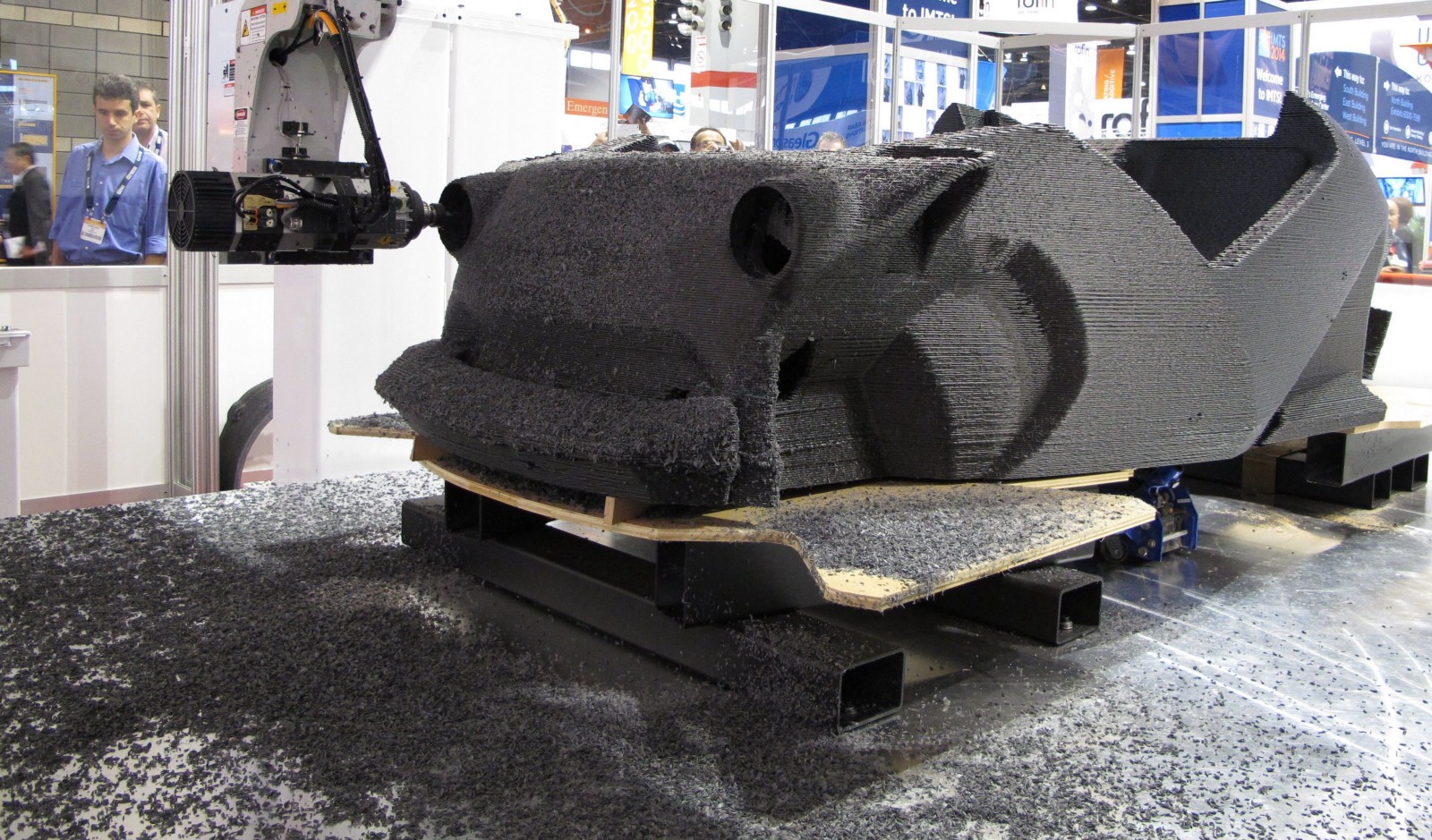

For example, a team lead by Local Motors and the Manufacturing Demonstration Facility was able to print the body of a car, using ABS plastic reinforced with carbon fiber. While this is an amazing proof-of-concept, one major challenge is that the printed parts do not match the performance of their molded analogs. In the case of the Big Area Additive Manufacturing (BAAM) machine that was used to fabricate the car, the printed material is only about half as strong as its molded counterpart. Although the automated high-precision machinery available today is impressive, there is clearly significant room for improvement on the materials side of the equation.

The in-progress body of the first 3D-printed car. (Image: Business Wire)

The in-progress body of the first 3D-printed car. (Image: Business Wire)

The beautiful future of democratized manufacturing promised to us in the craze of desktop filament printers has not been delivered. Instead, most of us received a finicky factory for cheap trinkets and toys. I believe that the maker movement is ultimately limited by the materials that are available. You can see for yourself in the cost models above that there are clearly a huge number of cases where “small batch” additive manufacturing can win on cost and time — not to mention the deep reductions in both input energy and generated waste that are afforded by 3D printing. If only we had the materials…

Fundamentally, this is a chemistry problem. This is why I founded polySpectra — to bring advanced materials to additive manufacturing. Our process, termed functional lithography, enables a new family of high-performance materials to be directly fabricated in a single step. Our goal is to unlock new applications of additive manufacturing by attacking the crux of the problem. At polySpectra, we’re working to make additive manufacturing inexpensive, but not cheap.

Mirror: https://medium.com/@rawwerks/additive-manufacturing-is-cheaper-than-you-think-b21fee9a5533