“The turntable of the talking machines is comparable to the potter’s wheel: a tone-mass is formed upon them both, and for each the material is preexisting. But the finished tone/clay container that is produced in this manner remains empty. It is only filled by the hearer.” -Adorno

I am often asked to describe how science has influenced my music (and sometimes vice verse). I often respond practically, pointing out particularly scientific aspects of my workflow: building instruments, writing code, neurotically tweaking parameters. Or I might wax philosophical, probing loftier comparisons. In science, you can never be right. In art, you can never be wrong. In both, what’s “hot” isn’t always what’s good. etc. Here, I thought it would be fun to get metaphysical with a core scientific concept: resonance.

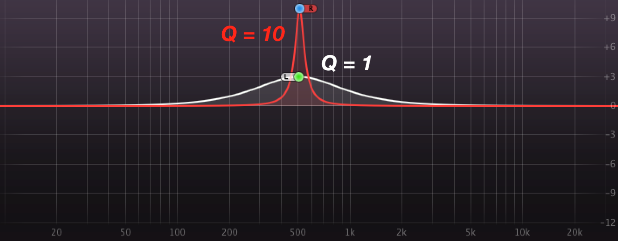

Physically, resonance is a fundamental property of oscillatory systems: frequencies “on resonance” are easier to excite because of a natural tendency of the system to vibrate at those frequencies. Resonance is at play everywhere; it connects the timbre of instruments with their physical shape, the color of dyes with their molecular structure, the period of a swing with the length of the chains. A key characteristic of a resonator is its quality factor, or Q factor. The Q factor quantifies how strongly the resonator responds when excited at its natural frequency: a high-Q resonator has a very sharp response on resonance, while a low-Q resonator has a weaker, but broader response centered at the resonant frequency. The lifetime of the response is proportional to the Q factor: low-Q resonances decay quickly. We will stick with this basic description here, but for the musically inclined and scientifically curious I would highly recommend Eric Heller’s Why You Hear What You Hear: An Experiential Approach to Sound, Music, and Psychoacoustics, which includes an intuitive introduction to wave physics, where resonance rules.

The Q factor quantifies the how sharp the resonant response is.

The Q factor quantifies the how sharp the resonant response is.

Metaphorically, resonance is about the ability to excite people: to move, engage, connect. When we resonate with something we get it, we feel it, we’re into it. We can describe both art and audience as being composed of resonators: an individual’s taste has unique resonant frequencies, a piece’s artistic statement has a distinct spectrum. We can imagine a purist as a high-Q resonator, an eclectic as a broadband receiver. Perhaps we can characterize the continuum between art and entertainment by the difference in Q factors. In pop music and network television—the aim is to be as broadband as possible: reach the largest audience by working with catchy melodies and cultural clichés. The inevitable consequence of these low-Q resonators is a short lifetime: the media is rapidly consumed and quickly becomes dated. The high-Q scenario of “High Art” is the opposite. The resonant audience is small—very few people “get it”. Yet the impact within those small circles is huge, and the decay time is much longer. Which composition from 1952 is more relevant today: John Cage’s 4’33” or the #1 Billboard Hit “Blue Tango” by Leroy Anderson? (It is left to the reader to decide if physical Q factor is correlated with artistic quality factor.) Here, I will stick to a first-order comparison; in both physics and art the reality of the situation is complicated by feedback and non-linearities. Cultures, fields, movements, genres and social networks are all important examples of feedback mechanisms.

In making art, we hope it will resonate strongly with people. We make it to share, we want to connect. The transcendent potential of art lies in its ability to communicate experience, to stir intangible emotion. This crystallized for me during a recent experience with Janet Cardiff’s The Forty Part Motet at the Cloisters in Manhattan. The installation is a reimagination of a 16th century Renaissance motet: forty individual speakers in clusters of five line the perimeter of a small elliptical chapel, each playing a single voice. The synergy between the space and the piece created an ethereal yet intimate environment, completely serene. We stayed for three presentations of the fifteen-minute-long work—in each audience dozens were moved to tears. I could feel the music resounding within me, continually finding new connections to my own world. I had spent the prior year determined to finish my album Marrow, a project that had been on the backburner for many years, but that I felt an immense pressure to complete and release. We had just finished mastering the record, and the weight of completion was starting to sink in. The prospects for putting it out into the world made me incredibly anxious; I was excited to finally share this story, but also terrified by how it would be received. The album is enormously intimate and personal, which seeded my existential unease: would it resonate with people? But here in this solemn space, surrounded by forty unique yet interconnected voices, immersed in an ageless song, bobbing adrift between nodes—my anxieties dissolved. I left uplifted. Marrow will find its audience, on resonance.

Resonant electromagnetic modes of a sphere, mapped onto my head.

Resonant electromagnetic modes of a sphere, mapped onto my head.