Our everyday sense of color is based on the absorption of light. If our shirt appears red, a dye or pigment is absorbing all of the colors except for red. By contrast, structural color is based on reflection, not absorption. Structural color is an important consequence of the fact that light is a wave. We can define the color either through the wavelength — the physical distance between the repeating crests, or the period — the amount of time for the wave to repeat. The wavelength (length) and period (time) are connected by the speed of light (length/time). Because of the periodic nature of light waves, the microscopic geometry of a material is intimately connected to its optical properties. For visible wavelengths of light, materials need to have periodic micro- or nano-scale features to exhibit structural color. Although these assemblies are too small to see with the naked eye, their appearance is an optical signature of their shape.

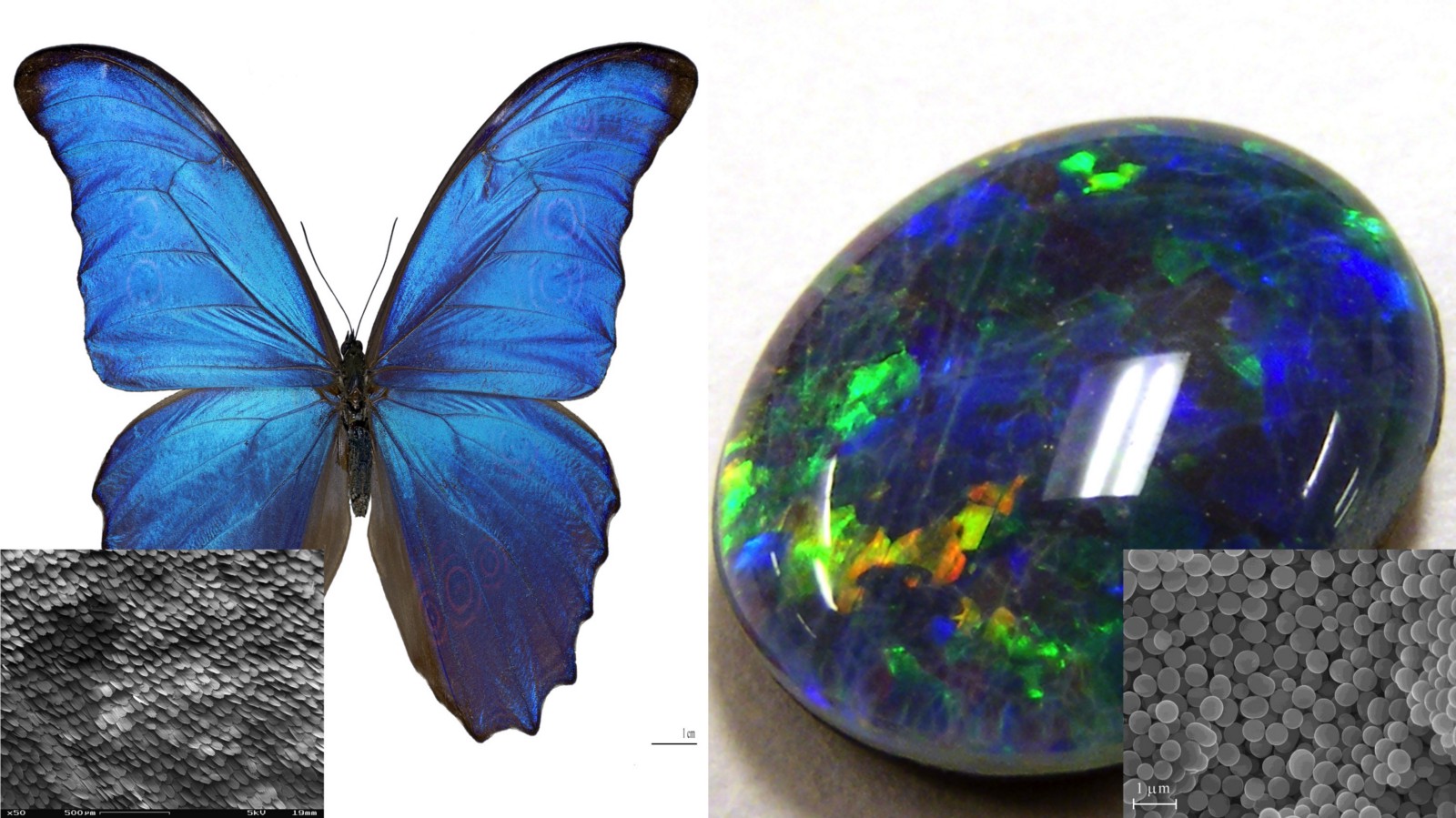

Electron microscopy reveals the nanoscales on a butterfly wing, and the nanospheres inside and opal. (Images from Wikimedia Commons, except the opal micrograph, which is by George Rossman at Caltech.)

Electron microscopy reveals the nanoscales on a butterfly wing, and the nanospheres inside and opal. (Images from Wikimedia Commons, except the opal micrograph, which is by George Rossman at Caltech.)

A number of beautiful examples of structural color can be found in nature, including the iridescent hues of butterfly wings and opals. The brilliant structural color of butterflies is due to arrays of nano-sized scales that texture their wings. Opal gemstones are composed of densely packed silicate spheres — their chemical composition is identical to glass, but their microstructured geometry leads to wildly different optical properties. The secret ingredient for structural color is the periodicity of the material — the color will shift if we change the size or spacing of the repeating scales or spheres. Additionally, the more well-ordered the arrangement, the brighter the opalescence and sharper the color. As we rotate the opal, the colors shift because our eye is now aligned with differently spaced arrangements of packed spheres.

To see structural color in action, I’ve prepared a simulation of the simplest periodic material: an alternating multilayer. Watch how three different wavelengths of light interact with this periodic multilayer structure:

In each case, light from the source on the left interacts with the multilayer structure in the middle. There is no absorption occurring in this simulation, only reflection. The first two non-resonant wavelengths can pass through the multilayer despite the reflections at each interface. In the third case, the wavelength matches the optical period of the repeating structure and the reflected waves add — this is called constructive interference. This resonance creates a ‘photonic stop-band’ around that wavelength, reflecting almost all of the light backwards.

One important consequence of the photonic stop-band is that the color you see with your eye depends on which side of the multilayer you are looking at. On the same side as the source, the reflected light will be tinted the same color as the photonic stop band. On the opposite side, you will see the complementary color, because the wavelengths within the stop-band cannot propagate through the material. This phenomenon makes multilayer structures very useful as filters and color-selective mirrors — different wavelengths of light can be directed to unique locations. These types of periodic structures are used in many applications today, such as laser cavities, solar control window films, and optical filters.

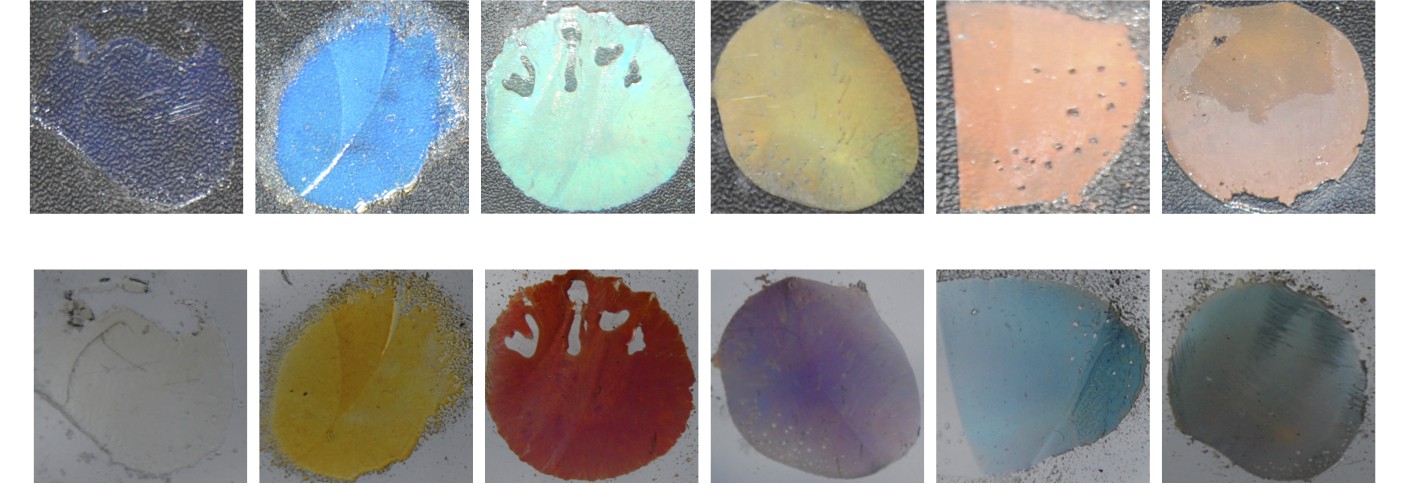

A series of polymer multilayer films imaged in reflection (top) and transmission (bottom). (Image courtesy Benjamin Sveinbjornsson, from our PNAS paper together.)

A series of polymer multilayer films imaged in reflection (top) and transmission (bottom). (Image courtesy Benjamin Sveinbjornsson, from our PNAS paper together.)

The images above depict plastic films composed of alternating nanolayers of two different kinds of polymers. These films are similar in structure to the multilayer stack that we simulated above, except that they have hundreds of alternating polymer layers. Either of the two polymers would be transparent on its own. However, by alternating between the two different materials with nanoscale periodicity, we can fabricate materials with tunable structural color. In the image below, we were able to tune the reflected color across the entire visible spectrum by blending uniquely-shaped polymers together in different ratios.

A series of blended bottlebrush block copolymer films, which self-assemble to ‘photonic paint’. By changing the blending ratios of the materials, we were able to continuously tune the structural color from the ultraviolet into the near infrared. (From our Angewandte paper, image courtesy Victoria Piunova.)

A series of blended bottlebrush block copolymer films, which self-assemble to ‘photonic paint’. By changing the blending ratios of the materials, we were able to continuously tune the structural color from the ultraviolet into the near infrared. (From our Angewandte paper, image courtesy Victoria Piunova.)

My collaborators and I are working to develop DIY heat-reflecting window coatings with this technology, which will selectively reflect infrared light to reduce the need for air conditioning. Instead of using precision engineering to directly pattern the nanostructures, we are employing self-assembly to develop an inexpensive ‘photonic paint’. Cheaper methods of accessing nanostructured materials might enable structural color to replace traditional dyes and pigments in everyday applications. As Michael Braungart and William McDonough point out in their book The Upcycle, some colors (green dye in particular) cannot be manufactured without the use of toxic components. In contrast, multilayer films can be constructed out of non-toxic materials, free of any additives that might leach into the environment. As a result, structural color might finally enable a green green.

Want to dive deeper?

- Make your own simulation with the Ripple Tank App from Paul Falstad

- Orfanidis wrote an amazing, free book on electromagnetic waves

- Joannopoulos wrote an amazing, free book on photonic crystals

- Berkeley Lab wrote a very nice article about our work on paintable photonic crystals for energy-efficient windows

Quiz question: In my video, why does a little bit of light from the wavefront make it through in the 3rd simulation, even though the wavelength is resonant?

Mirror: https://medium.com/@rawwerks/what-is-structural-color-536ee6fe46d4